I came across this essay during my surfing and felt like I wanted to share it.

International Socialist Review Issue 47,May–June 2006

S P E C I A L F E A T U R E. WHAT DO SOCIALISTS SAY ABOUT...

Human Nature?

By ELIZABETH TERZAKIS

MANY PEOPLE think socialism is impossible—not because the ruling class is too powerful or the world’s resources are too limited, though many people believe this—but because “human nature” will not allow it. They think “people are too lazy,” “too passive,” “too greedy,” “too self-absorbed,” “too violent,” “too ambitious.” They think that people are inherently racist, sexist, and homophobic, that they can’t help but hate people from other countries, cultures, and religions. They think that “people like being told what to do” and “people can’t think for themselves” and “people like to boss other people around.” Nevermind that some of these “inherent” traits are contradictory. Together they work to prevent socialism in the minds of many. And, as if all this weren’t enough, human nature is thought to be not only negative, but permanently fixed: “There will always be good people and evil people” and “You can’t change human nature.”

It is no surprise that people often think this way. Marx once said that the ruling ideas of any age are the ideas of the ruling class. The ruling ideas about human nature under capitalism—that it is static, and for the most part awful—greatly benefit the capitalists. On the one hand, they suggest that, because of traits inherent to human beings like greed, ambition, and a tendency towards violence, capitalism—which rewards greed and requires violence—is not only the best and most efficient economic system ever, but also the most natural.

On the other hand, such ideas make it possible to blame the enormous inequality and suffering produced by the system on the “natural” defects of certain individuals. If it is natural for some people to claw their way to the top, it is also natural for others to remain stuck in squalor at the bottom.

Socialists argue something quite different. We say that human nature is flexible and multifaceted, and that the behaviors of human beings are shaped by their social circumstances. We are all capable of greed as well as generosity; which one gets expressed has more to do with the values of a society than with the inborn tendencies of the individual. As Karl Marx put it: “the human essence is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In its reality it is the ensemble of social relations.”1

From a socialist perspective, there is such a thing as human nature, but its most prominent feature is its changeability. What makes us distinctly human is our ability, not only to change as our circumstances change, but to create new and different social relations and then adapt to them. Socialists argue that if humans could create capitalism, humans can create socialism.

There is a lot at stake in this argument.

If it is natural for humans to engage in the practices that capitalism supports or requires, then any attempt to change the system is pointless. In the words of anthropologist Ashley Montagu:

If we are killers by nature, we are wasting precious time, with the minute hand approaching midnight, in teaching people to think independently, in rehabilitating criminals, in compensating people for unlucky beginnings, in trying to improve the physical and mental health of all human beings. We should instead be devising ways of discharging our aggressive drives—[behavioral physiologist Konrad] Lorenz suggests sports as a good way—and at the same time building up our individual defenses against the inevitable holocaust.2

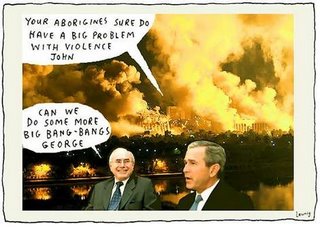

Montagu was writing in 1975, but in 2006 this passage reads, not like a description of a potential dystopia, but like a page from a twenty-first century yuppie handbook. All it needs is an accompanying illustration of a man in sleek lycra shorts unloading a $3,000 bicycle from a Hummer and cursing at a homeless person for obstructing the sidewalk that leads to the gym. Today, when the ruling class controls weapons and oversees business practices that threaten the existence of the planet, promoting a socialist understanding of human nature is not only correct, but urgent.

From the beginning the tendency to revert to human nature to justify social and economic structures and to explain their failures has been present from the very beginning of United States history. James Madison rationalized the system of checks and balances between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches that, at the time, distinguished the U.S. form of government, on the basis of a negative view of human nature.

“Ambition must be made to counteract ambition,” he wrote. “It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature?”3 No allowance is made for the fact that the framers of the U.S. Constitution were the richest men in the country at the time, busy enslaving Africans and massacring Indians, and that they, as rich white men, rather than humans as a species, were ambitious and aggressive and needed to be reined in.

The idea that capitalism’s failures should be blamed on the poor also got an early start. Eager to please their ruling-class benefactors, scientists and scholars have always been willing to develop theories and misinterpret or fabricate experimental results to support this notion. In the nineteenth century, eugenicists and “Teutonists” (think of an upper-crust Aryan Nation) fudged test scores and measured heads to produce what was considered scientific backing for the idea that poverty is the result of inherited weaknesses of character or intellect called “social inadequacy.”

The resulting conviction that “poverty begets poverty” led to forced sterilization and enforced illiteracy; if the children of illiterate parents cannot be taught to read, the argument went, why waste money on schools?4

This “scientific racism,” which was applied to all members of the lower classes regardless of skin color, existed alongside of and in combination with the racism used to rationalize the enslavement of Blacks and the genocide of Native Americans. An excellent example of the way these ideas came together is a statement by Oxford University Professor Edward Freeman, who toured America in 1881, speaking to university and “learned society” audiences.

According to Freeman, and to the delight of his “learned” listeners: “the best remedy for whatever is amiss in America would be if every Irishman should kill a Negro and be hanged for it.”5

At the start of the twenty-first century, one is struck not only by how shocking, but also by how shockingly familiar this statement sounds. In September of 2005, conservative talk show host Bill Bennett—who was secretary of education during the Reagan administration and director of drug policy under the first George Bush—told listeners of the Salem News Network: “I do know that it’s true that if you wanted to reduce crime, you could—if that were your sole purpose—you could abort every black baby in this country, and your crime rate would go down.”6

Though patently reactionary, statements like Bennett’s are not inconsistent with current ruling class views on the causes of social ills and inequality. Earlier in 2005, Lawrence Summers—then-president of Harvard University—attributed the shortage of women professors in the sciences and engineering to “innate differences” between men and women and discounted the role of discrimination in hiring practices and career advancement. According to Summers, “Research in behavioral genetics is showing that things people previously attributed to socialization weren’t” really the result of social influences but rather a lack of “natural ability.”7

What sort of “research” supports these views? That of the sociobiologists of the seventies and the evolutionary psychologists of today. Sociobiologists attempted to use evolutionary explanations drawn from the study of animals to understand the behavior of humans.

Starting from an assumption of the “universality” of a particular trait, they would assert (but not prove) that there must be a genetic explanation for that trait. According to the sociobiologists, aggression, competition, gender hierarchies and a long list of other human traits and tendencies are biologically determined and therefore permanent features of human society. As anthropologists Marshall Sahlins and Michael Ghislein point out, sociobiologists revised the theory of natural selection to reproduce almost verbatim “the precepts of laissez faire capitalism.”8

To make their case, sociobiologists used research in non-human animals, what Kohn calls “conceptual pole vaulting,” noting that “most forms of human violence are not analogous, let along homologous, with animal aggression. Only human behavior is saturated with cultural meaning, organized around symbols, [and] conceived in terms of long-range rationally devised purposes.”9

The 1990s saw sociobiology’s reincarnation in the form of evolutionary psychology. Evolutionary psychologists argue that humans have countless instincts, all genetically programmed into separate “modules” in our brains, and that these instincts are responsible for most of what passes for “normal” human behavior—things like men being “naturally” attracted to younger women with “perky breasts.”10 They argue that human beings stopped evolving during the Pleistocene era that ended 10,000 years ago.

Lo and behold, the instinctive processes of a “Stone Age brain” dovetail—if not seamlessly, then inevitably—with the demands of market capitalism. According to one defender of evolutionary psychology, “Those who command higher status in social hierarchies have better access to material resources and mating opportunities.

Thus, evolution favors the psychology of males and females who are able successfully to compete for positions of dominance.”12 Evolutionary psychologists’ hypotheses gloss over the fact that little is known about ancient hunter-gatherers and the problems they faced. As philosopher David Buller points out, “We don’t even know the number of species in the genus Homo let alone details about the lifestyles led by those species.”12 Attempts to generate theories on the basis of currently existing hunter-gatherer groups break apart on the basis of sheer diversity; there is little consistency among the practices of modern-day hunter-gatherers—besides a general egalitarianism (no support for the evolutionary psychologists there!)—and no way of knowing which are more like our genetic ancestors.

Mostly, the evolutionary psychologists recycle modern stereotypes and project them back over human pre-history.13 ,but perhaps most significantly, the theory is inconsistent with what little is currently understood about genetics and the human brain. If the claims of evolutionary psychology were accurate, and most of the structures of the brain were genetically determined, it would stand to reason that the human genome would be much larger than that of less cognitively developed animals to allow for the extra complexity of our brains.

But this is not the case. Humans have the same number of genes as mice. And even if 50 percent of our genes are involved in building brain structures, most are dedicated to sensory rather than higher cognitive functions like the ones that evolutionary psychologists are attributing to genetically determined instinct modules.14

Like the eugenicists of the turn of the last century and the sociobiologists of the 1970s, the evolutionary psychologists of today provide scientific cover for existing unequal social relations. These variant strains of biological determinism have already been exhaustively covered in this journal,15 so I won’t go into any more detail here. Suffice it to say that, though they provide little proof of anything except their authors’ prejudices, each new crop of poorly supported nonsense is picked up by the mainstream press and pounded into the popular psyche, then retracted months or years later in a footnote or a sidebar.

The Yanomami are from Mars and so is everybody else Take, for example, Napoleon A. Chagnon’s studies of the Yanomami. In the 1960s and 1970s, anthropologists like Chagnon considered the Yanomami of Venezuela and Brazil to be prime examples of the darker side of human nature. “Engaged in endless wars over women, status, and revenge, the Yanomami were supposed to exemplify the natural human condition of eons past. Some people took Chagnon’s work to imply that aggression is in our genes.”16 Chagnon’s book, Yanomamo: The Fierce People, was assigned reading in introductory college anthropology courses across the U.S.—the only anthropology that students who did not go on to major in the subject would ever read.

Unfortunately for those students, alternative interpretations of Yanomami behavior did not become public until more than thirty years later. Although anthropologists had been debating the source of the Yanomami’s “fierceness” almost from the moment Chagnon published his book, the debate was not popularized until a journalist accused Chagnon of starting the Yanomami wars himself. Anthropologist R. Brian Ferguson’s more reasoned view—that the Yanomami warfare was neither pre-historical nor the fault of a single anthropologist, but could be traced to the colonial era—had been published in 1995 but largely ignored by everyone outside of the professional community. According to Ferguson, the introduction of scarce supplies of manufactured goods produced competition; the simultaneous introduction of steel weapons ensured that competitive conflict, when it occurred, was more deadly.

Although there is still some dispute over who, exactly, is responsible for Yanomami aggression and when it began, “no one paying attention to this controversy still claims that Yanomami wars can be understood without taking into account the tribe’s highly disrupted historical circumstances.”17 That is, rather than proving that humans are naturally violent, a closer look at the Yanomami reveals them changing their behavior in response to drastic alterations in &# 220;the ensemble of social relations”: the disruption of kinship and sharing patterns by the early slave trade, disease, game depletion, and other fallout from the introduction of Western-style “free trade.”

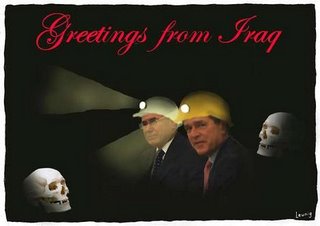

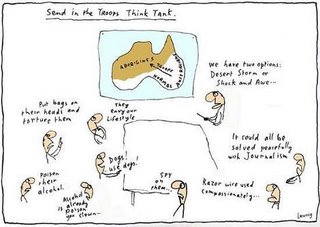

The idea that aggression and its correlative violence are human universals is a favorite of biological determinists. Fortunately, it does not hold up to anthropological or archaeological scrutiny, or even to a casual survey of the world today. Most people are nonviolent most of the time. If humans were naturally violent and prone to kill, it would not be necessary to put soldiers through the rigors of boot camp to make them fit for war. There would be no need to dehumanize the soldier or the enemy, and soldiers would not be returning from battle with shattered psyches. But in reality this is not the case. Soldiers are taught to deny instincts and reason. They are taught to view their opponents as less than human in order to make them easier to kill. Even so, many return from battle so broken psychologically and emotionally that they cannot function in society. According to the February 2006 Journal of the American Medicinal Association, 20 percent of soldiers returning from the occupation of Iraq “met the risk criteria for a mental health concern,” and 10 percent were actually diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), many after killing or seeing people killed.

What is human nature?

Although the human race has seen enormous and rapid cultural evolution, human beings’ basic physical needs have remained the same for hundreds of thousands of years: we need air, water, food, shelter, or other protection from the elements, sleep, parenting for the young, and sex to propagate the species.18 These general needs are accompanied by a set of specific abilities: because humans have large brains, walk upright, have hands with opposable thumbs, and vocal chords that allow speech, we are able to use our physicality, our bodies and brains and the five senses they afford us, in ways that other creatures can’t. First and foremost, we work in a distinctively human way and, through social labor, we change our environment and the conditions that determine our “nature.”

Friedrich Engels, writing in 1876, placed labor at the very center of human development: “[Labor] is the prime basic condition for all human existence, and this to such an extent that, in a sense, we have to say that labor created man himself.”19 Engels goes on to attribute changes in human anatomy to work in general and working with tools in particular, comparing the bone structure of the human hand to that of other primates and noting “the great gulf between the undeveloped hand of even the most man-like apes and the human hand that has been highly perfected by hundreds of thousands of years of labor.”20

In addition to working with tools, humans have always lived and worked in groups: “The development of labor necessarily helped to bring the members of society closer together by increasing cases of mutual support and joint activity, and by making clear the advantage of this joint activity to each individual.” From cooperative labor arose the need to speak and the development of language: “In short, men in the making arrived at the point where they had something to say to each other. Necessity created the organ; the undeveloped larynx of the ape was slowly but surely transformed.”21 The development of complex systems of language allowed for human social consciousness: the transmission of culture and history from generation to generation.

Of course it can be argued that animals also work: they hunt, gather, and in some cases store food; they build nests and dens and tend their young. Some cooperate; some communicate, albeit nonverbally; some even use tools. But the work done by animals is mostly instinctive and unchanging. Otters may use stones to crack open sea urchins but they can’t invent a sea urchin cracker. Beavers take down trees to build their dams but they’ll never use a chain saw. Whales may communicate through songs, but they can’t write lyrics or mass produce CDs. Only humans have the ability to record their history and create art. Only humans can conceive of a project, plan out the various steps to completion, and reflect with satisfaction on a job well done. Only humans can invent and construct complex tools that alter the environment and allow for enormous increases in productivity—tools that enable us to make a lot more stuff with a lot less effort.

By acting on nature to produce their subsistence, human beings change themselves. Laboring socially, humans change the material forms of what Marx called their means of production. These engender new social relations, allowing, in the end, for the distinctive variability of human behavior through history, and from one society to the next.

The impact of capitalism

Marx observed that, under capitalism, human productive capacity increased so much that, for the first time in history, it was possible to have enough of everything for everybody. What’s more, the satisfaction of basic needs and the ways in which they were satisfied led to the development of more complicated needs. Crowded living conditions create a need for systems of sanitation. Complex machinery creates a need for higher education. These complications further the development of human tastes and abilities, and could lead, under conditions of socialized, planned production, to the fullest expression of human nature:

Just as the savage must wrestle with Nature to satisfy his needs, to maintain and reproduce his life, so must civilized man, and he must do so in all forms of society and under all possible modes of production. With his development this realm of physical necessity expands as a result of his wants; but, at the same time, the forces of production which satisfy these wants also increase. This realm of natural necessity expands with his development, because his needs do too; but the productive forces to satisfy these expand at the same time.

Freedom, in this sphere, can consist only in this, that socialized man, the associated producers, govern the human metabolism with nature in a rational way, bringing it under the collective control instead of being dominated by it as a blind power; accomplishing it with the least expenditure of energy and in conditions most worthy and appropriate for their human nature.22

But there was (and is) a problem. Capitalists were not (and are not) “rationally regulating their interchange with Nature.” They compete in an irrational and unplanned manner with an eye towards maximizing profit rather than meeting human need. Promoting “conditions most favorable to, and worthy of, their human nature” does not concern them either. Instead, their interests lie in getting people to work as hard as possible for as little as possible. And so, despite its potential to do so, capitalism does not allow most of humanity to satisfy its basic needs with “the least expenditure of energy.”

Instead, it works some people to the bone while others are thrown out of work. Under capitalism, advances in technology like automation create, not leisure, but unemployment for some and overtime hours of mind-numbing repetitive labor for the rest.

Capitalism created the conditions for the fullest expression of human nature, but simultaneously denied them to the vast majority of humanity by directing all the wealth up to the tiny minority at the top of society. Members of the ruling class collect homes and cars and gadgets, attend first-rate universities, travel the world, eat exquisite food and drink exquisite wine, enjoy operas and symphonies and rooms full of fine art, and develop whatever talents or abilities they have, and often those they do not. Meanwhile, the majority of the working class struggles from day to day to make ends meet, with a few weeks off per year to develop ourselves in areas other than work—if we’re lucky. Capitalism not only stunts further human development, it is also a stupendous failure when it comes to providing for the basic needs of most people. Every day, all over the world, tens of thousands of people starve or die young of curable diseases.

Far from being naturally adapted to capitalism, most humans are battered or broken by it. If it doesn’t straight out kill them, it stunts their physical and mental development; their intellects are neglected, their artistic talents remain undiscovered or unappreciated, and the distinctively human capacity to engage in creative, socially useful work is reduced to a commodity worth only as much as the capitalist can pay and still turn a profit.23Can humans do socialism?

Even those who recognize that capitalism thwarts and distorts human nature—and that we now possess the means to eliminate inequality and want—may still wonder whether humans are capable of the kind of truly egalitarian society that socialists envision. Forced to compete with each other for limited opportunities, compelled to work mindlessly at jobs they don’t like, encouraged to view themselves and those around them as commodities, many people might not seem prepared, at any given moment, to plan and create, “in place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms…an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.”24 We are swimming (or, more accurately, treading water) in what Marx called “the muck of ages”—racism, sexism, homophobia, competitiveness, conformity, passivity, insecurity—all the ideas capitalists require to divide and enervate the masses and maintain their minority hold on power.

And it is easy to feel, after a few hundred years of capitalism, that things have always been the way they are now and always will be. Luckily for us, this is simply not true. Capitalism is a fairly recent development, and prior to the rise of class society some several thousand years ago, human society was not characterized by classes or inequality or systematic warfare. There are class-free societies on the planet at this very moment, societies that are “egalitarian, cooperative, and on the move.”25 All of the Ju/’hoansi (!Kung) Nharo Basarwa (San or Bushmen) from Ngamiland, Botswana, lived until just recently in societies where egalitarianism—notably along gender lines—was the rule.

As some communities shift from nomadism to sedentism, this has started to change—not due to some “resurgence” of human nature, but rather to “the adoption of the economics and attitudes towards gender from non-foraging neighbors [that] facilitates the emergence of gender inequality.… [In addition, some] current development programs designed by Westerners exclude women and contribute to the increase in gender inequality which is emerging in these societies.”26

While the existence of egalitarian hunter-gatherer societies is reassuring, we in the U.S. don’t have to look quite so far to see the tendencies in human beings that make socialism possible. After Hurricane Katrina, in the face of government neglect that created an unnatural disaster, ordinary people right here in the U.S. opened their homes, donated money, collected supplies, and devoted their time to help people they had never met. Those victimized by the storm risked their lives to save others and demonstrated their ability to do what the government wouldn’t—act like human beings. San Francisco paramedics Larry Bradshaw and Lorrie Beth Slonsky were part of a group of visitors and locals trapped in the city who pulled together to try and make it safely out of the city only to be, now famously, stopped by police at the bridge to Gretna. They witnessed countless acts of humanity and self-sacrifice:

What you will not see [in mainstream reports on the disaster], but what we witnessed, were the real heroes and sheroes of the hurricane relief effort: the working class of New Orleans.The maintenance workers who used a forklift to carry the sick and disabled. The engineers who rigged, nurtured and kept the generators running. The electricians who improvised thick extension cords stretching over blocks to share the little electricity we had in order to free cars stuck on rooftop parking lots. Nurses who took over for mechanical ventilators and spent many hours on end manually forcing air into the lungs of unconscious patients to keep them alive.

Doormen who rescued folks stuck in elevators. Refinery workers who broke into boat yards, “stealing” boats to rescue their neighbors clinging to their roofs in flood waters. Mechanics who helped hotwire any car that could be found to ferry people out of the city. And the food service workers who scoured the commercial kitchens, improvising communal meals for hundreds of those stranded.

Ordinary people expressing their ability to find creative solutions to extraordinary problems, their desire to do socially useful work, their willingness to share, and their willingness to risk their lives for others. If you pay attention, the elements of human nature necessary for socialism—despite their constant repression by the forces of capitalism—are evident during disasters and in everyday living.

There is nothing about human nature that makes socialism impossible, but there is also nothing that makes it inevitable. According to Marx, people make their own history but not in circumstances of their own choosing.28 If we want socialism—and the possibility of developing human nature to the fullest—we will need to organize and fight for it. This may seem like a pipe dream given the low level of class struggle in the U.S. at this time. But a socialist conception of human nature also allows us to understand how groups of people that for a long time appeared to be hardwired for one set of behaviors—like not fighting back—can transform radically and rapidly in response to social changes.

For example, in a recent interview, Zapatista leader Subcomandante Marcos noted certain alterations in the behavior of the indigenous women of Mexico who became leaders in the Zapatista National Army for Liberation (EZLN by its Spanish acronym):

The first change is made internally among the relationship between women. The fact that one group of indigenous women, whose fundamental horizon was the home—getting married quite young, having a lot of children, and dedicating themselves to the home—could now go to the mountains and learn to use arms, be commanders of military troops, signified for the communities, and for the indigenous women in the communities, a very strong revolution.

It is there that they started to propose that they should participate in the assemblies, and in the organizing decisions, and started to propose that they should hold positions of responsibility. It was not like that before…[After passing their training] a group of insurgent women are now the ones who are superior, and when they head back down to the communities, they now are the ones who show the way, lead, and explain the struggle. At first this creates a type of revolt, a rebellion among the women that starts to take over spaces.

Among the first rebellions is one that prohibits the sale of women into marriage, which used to be an indigenous custom, and it gives, in fact (even though it’s not on paper yet) the women the right to pick their partner.

This rebellion in the nature of the Zapatista women—from passive to active, from domestic servitude to public leadership—occurred as a result of the encroachment of the modern Mexican state on the indigenous community, the consequent disruption of traditional means of securing a livelihood, and the emergence of the Zapatista struggle and the radicalizing impact it has had on the consciousness of the oppressed. While it is impossible to predict the exact changes in the ensemble of social relations that will wake the sleeping giant that is the U.S. working class, recent protests against attacks on immigrant rights show that millions of people in this country are ready and willing to fight. If they are not (yet) fighting for socialism, don’t blame human nature.

Elizabeth Terzakis, a member of the International Socialist Organization in the Bay Area, is an instructor at Cañada College in Redwood City, California.